A Thick Description Of A Deep Time

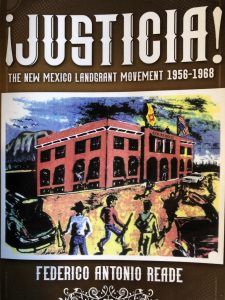

¡JUSTICIA! By Federico Antonio Reade (Albuquerque, 309 pages)

A UNM UNDERGRADUATE named Federico Antonio Reade called me in Santa Fe in the fall of 1980 asking to record my recollections of the Rio Arriba County Court House Raid — a northern New Mexico rebellion that already was fading beneath a wash of scholarly interpretation. I had been the only journalist (and the only visible Anglo) anywhere near that rural court house on June 5, 1967, when Reies Lopez Tijerina and a dozen armed men — in the role of dispossessed heirs to historic land grants — stormed up the wooden stairs.

They were there to free their jailed brethren in Tijerina’s land-grant alliance (Alianza) and, in all probability, to shoot the district attorney who was responsible for arresting them. He wisely was never there and his prisoners were released by an annoyed judge before the Aliancistas stormed. Tijerna was an intimidating leader — a mission-driven believer from the lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas whose militant oration agitated the half of New Mexico who did not know much Spanish. The first time I covered him, in October 1966 at the takeover of Rio Arriba’s natural wonder called called Echo Amphitheater, I asked what he would do if federal law enforcement officers counter attacked. He had no answer, at least in English. Directly, standing on a USFS picnic table he unfurled a Spanish oration, and his Aliancistas cheered as mimicked a trembling pendejo (dirty slang for fool).

When Federico called fourteen years later I was tired of telling my story that usually begins with Echo Amphitheater. So I refused his invitation at first. Then an opportunity occurred to me. I would stand for his video interview if he would show me around the Albuquerque South Valley. I had left a 15-year career with the news wire services in order to take a position as the Santa Fe bureau chief for the Albuquerque Journal, the statewide daily. The editors were testing me with a prodigious assignment: go around the state and write a series on what people were saying about the approaching election. A geographical gap in my coverage was the barrio, where Federico lived.

On meeting him there, my first impression was: this is going to be an adventure in cultural diversity. He was Chicano, from his unlaced work boots to his dark shades that barely concealed a scarred eye. He set up his camera and I told my story. Then I drove as he navigated the South Valley, avoiding places where he said we should not go, and he introduced me to a family that talked politics. He spoke from time to time in an idiom now known by the cryptographic metaphor “code switching,” meaning skillfully weaving two languages together, depending on the situation. If it was a test, I failed. I thought that chingon was an insult or gabacho was racist.

Forty years later, Federico is a literary code switcher with a PhD based on his lifetime study of the Court House Raid and its causes. He has just published a book about the land-grant movement with Spanish dialog and parenthetical English transtlations. Reading ¡JUSTICIA! is like living a few days with Nuevomexicanos speaking among themselves, using local expletives like samanabiche! among other transliterations. It is a good way to learn conversational Spanish.

Forty years later, Federico is a literary code switcher with a PhD based on his lifetime study of the Court House Raid and its causes. He has just published a book about the land-grant movement with Spanish dialog and parenthetical English transtlations. Reading ¡JUSTICIA! is like living a few days with Nuevomexicanos speaking among themselves, using local expletives like samanabiche! among other transliterations. It is a good way to learn conversational Spanish.

The book is not in the literary genre of the late UNM teachers Sabine Ulibarri or Rudolfo Anaya or in the stye of bilingo humorists like the late Jim Sagel (with characters like the one calling his pickup “una troca Ford.”) Federico is none of these. He is a polemicist. His scenes have messages:

— Some Nativos are confronting the Anglo employees of a logging company that has a brand new USFS timber lease. There is a new locked gate across a road used for decades by local cattle grazers. A deputy sheriff races to the scene, steps out of his cruiser and says, “Okay, what’s the problema? (It is, as they say in movie promotion, “based on” an actual event that ended with the company’s sawmill being torched).

—Two boys herding sheep on national forest land have them confiscated by a racist they call “the rinche” — the local idiom for “ranger” that rhymes with a swear word. (Based on repeated actual events in Carson National Forest).

For strangers, language is the first sign that New Mexico is a strange land. One day in November 1902 the first Congressional committee to visit the neglected territory stepped off a private rail car at the Las Vegas siding. They toured the divided city (Anglo east, Hispanic west) before convening their first hearing on a Senate bill granting the statehood withheld for half a century.

Chairman Sen. Albert Beveridge of Indiana, a progressive Republican and historian who would write a three-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln, said, “The committee noticed in driving around town that nearly all the signs were in Spanish where they have groceries and meat markets. What is the reason for that?” The witness, School Supt. Enrique Armijo, answered, “The majority of the people talk Spanish.” Beveridge asked him, “How long have you talked English? I observe that you talk a little bit brokenly.” Armijo responded, “Since 1874.” The official transcript shows exchanges like that persisting in hearings in Santa Fe, Albuquerque and Las Cruces. The committee went home and killed the bill. New Mexico waited another decade for statehood, but got a constitution and enabling act written in English and Spanish. The Pueblo and Navajo languages were ignored.

The main factor in predicting New Mexico elections even now is ethnic identity, which can work both ways when language becomes an issue. Candidates who say one thing in English and another in Spanish can be defeated, as was senior U.S. Sen. Joseph M. Montoya in 1976 after he compared his Republican opponent, lunar astronaut Harrison Schmitt, to a space monkey — using the slang “changito.” (I broke the “monkey speech” story.)

The dominant blurb in the front of ¡JUSTICIA! is by the New Mexico-grown writer Erlinda Gonzales-Berry (“Rosebud / Population 7”). She praises Federico for his “thick description,” a term coined by the late Clifford Geertz of Princeton in describing his own work as a non-structural cultural anthropologist. I had studied anthropology during a fellowship year at Stanford, and encountering his literary gift provided some relief from the kinship-and-taboo investigators. The new ethno-school lets native people tell their own stories. James Clifford, a Geertz successor who calls his own method “deep hanging out,” traveled everywhere, visiting places like Canadian First Nation museums to see how natives present themselves.

Oral historians are part of the same humanistic revolt, and their academic association invited Federico to show his videos at a big conference in Albuquerque in the early 1990’s, which I quietly attended. The audience of several hundred was particularly appreciative of one sequence on the big screen in which a Nuevomexicano in ranch clothes tries to narrate in English. He keeps reverting to Spanish and then freezing before the camera, restarting several times. They applauded. Here was the real thing. And so was Federico.

Suddenly, there in the dark, my verbal defenses went on alert. I knew Federico had a tape of my smooth journalistic report in which I stood looking at the camera as if it were my best friend and dressed in a sport coat and shined shoes (he had filmed a closeup of my shoes). If that video was cued up next the contrasting figure of myself would be met with derisive laughter, I was thinking.

See, the great Geertz wrote of his experiences in the field: “One of the psychological fringe benefits of anthropological research — at least I think it’s a benefit — is that it teaches you how it feels to be thought of as a fool and used as an object, and how to endure it.” But I had enough pendejo benefits, and so I was relieved when the chairman cut off the show, saying, “That will be enough.”

Federico never pretends to be an anthropologist, but lately any thickness of description, no matter how entertaining, can pass for professional anthropology. Geertz himself ridiculed the trend, bewailing, in his words, “various cooked-up and johnny-come-lately disciplines, semi-disciplines, and marching societies (gender studies, science studies, queer studies, media studies, ethnic studies, postcolonial studies, loosely grouped) the final insult, as ‘cultural studies’.”

Again, the author of ¡JUSTICIA! mixes stories with polemics, and the title of his book happens to have been Tijerina’s rallying grito, particularly near the end of his life. But Federico is circumspect about Tijerina’s character, as I am too. I interviewed his despairing daughter Rose upon the 25th anniversary of the Court House Raid. Dominated by her father, at age 17, she was the only female participant. She was arrested by state police and interrogated by a rough all-male squad.

Tijerina was seldom explicit about solutions to what for journalism-at-a-distance was “the land-grant issue.” He was a pioneer in the now prevailing American fulmination of free-wheeling political anger, and it produced headlines like: “The government stole our land!” The land-grant issue preceded him, going back to 1846 when Stephan Watts Kearney and his Missouri volunteers marched easily into the Santa Fe Plaza and raised their flag. The 150th anniversary of that occupation was conveniently forgotten. The ensuing 1848 treaty with Mexico that guaranteed property titles is remembered by the dispossessed as broken.

(My wife then was a welfare case worker in New Mexico’s rural north. She remembered visiting one family after gaining their trust, and the patriarch told her, “We are not poor!” To prove it he opened a trunk and his hand shook as he pulled out an old land-grant document.)

Federico’s account of the Court House Raid itself, though presented in a book disclaimed as fiction, can be corroborated. He does not write an apology about the violence. None is needed because no participant was ever convicted. Juan Valdez, who shot State Police Officer Nick Sais in the chest pleaded guilty and was pardoned by Gov. Bruce King as a favor to Rio Arriba Democratic patrón Emilio Naranjo. The sheriff, who was Naranjo’s son, and undersheriff Dan Rivera were beaten. A bullet ripped through the county jailer’s hat as he jumped out the sheriff’s office window, and another got him in the shoulder as he ran for cover outside. Baltazar Martinez, who may have fired that second shot, took me and deputy sheriff Pete Jaramillo hostage and shot up everything in sight, suddenly abandoned state police cars in particular, as he drove away with us in the deputy’s car. We escaped at a roadblock standoff.

The county jailer was Eulogio Salazar. On the frozen night of Jan. 2, 1968, as he opened the gate to his driveway in Tierra Amarilla after work, he was hijacked and beaten to death on a country road. He had been expected to testify in a February preliminary hearing that he saw Tijerina at the sheriff’s office door as the first shot was fired at him. In 1977, under political pressure to solve the Salazar murder, Atty. Gen. Toney Anaya (later to become governor) submitted an investigation report to Gov. Jerry Apodaca, but the key pages identifying likely suspects were sealed.

This coverup continues in its fifth decade. The case for a long time was regarded as New Mexico’s No. 1 unsolved murder. Coincidentally, 11 years later the lawyer who conducted the investigation, Michael Franke, was stabbed to death after hours outside his office in Salem, Oregon, where he was state corrections secretary. It was publicized as Oregon’s No. 1 unsolved murder, at least in the opinion of those who believed the smalltime thief convicted in the case was a fall-guy in yet another coverup.

¡JUSTICIA! goes beyond that era’s rhetoric and violence in passionate homages to New Mexico’s secretive religious confederacy called the Penitentes by early travel writers who equated them with the self-flagellating cults of medieval Europe. Charles Fletcher Lumis in “Land of Poco Tiempo” (1893) verified with glass-plate photographs his descriptions of their voluntary tortures culminating in a mock crucifixion, with a brother tied to a cross until he lost consciousness.

Federico tells a different story, of a reverent ritual enacted on Good Friday in moradas — unmarked windowless adobe sanctuaries in many New Mexico villages. Candles are extinguished during Holy Week until one light remains. When it is snuffed out the darkness (tinieblas) signifies, he says, “the moment Jesus died on the cross, symbolically teaching us that we complete our cleansing of the sorrows and distresses we all go through in our daily lives.” For a long time the Hermandad was excommunicated by the Catholic Church for heresy, an unpopular decision reversed decades later by the first Hispanic Archbishop, Roberto Sanchez. Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” was sold out night after night in New Mexico.

Federico Antonio Reade is a Penitente. In his informed view the Brotherhood’s main aim is caridad or caring for each other. His blurb advocate, Erlinda Gonzales-Berry who is an emeritus professor of cultural studies, says that “to be an Aliancista is to be an Hermano is pivotal to development of the narrative and Reade’s resolve to rewrite Nuevomexicano history from the bottom up.”

Tijerina was not a Penitente. And there are two possible reasons that he never would have been a practicing Hermano. One is that he was a Protestant evangelist by training, and the Penitentes are Catholic. The other is he was anti-semitic, condemning Israel as well as American Jews, and there is evidence that Penitente practices, such as the morada candleholders (like menorahs), were influenced by exiled conversos, sephardic Jews who were part of the first New Mexico colonizations.

Anyway, Tijerina moved away, living part-time in Mexico and dying of crippling diabetes in El Paso in January 2015. His Alianza is no longer active. But listen: the Brotherhood endures. I have seen some of these men in Truchas on a Good Friday, walking solemnly out of the historic church singing in a minor-key. Federico says the Penitente devotion involves songs venerating Jesus and the Holy Mother. The rich Nuevomexicano music accessible to both genders involves corridos, ballads that celebrate the legends of la raza. These can be topical, comprising the sixties protests, but they have been around for centuries. Federico prints the verses, including some of his own composition, at length. Lumis, the 19th century travel writer, was quite taken by the traditional songs and published words and musical scores in his influential book.

Another cultural thing that attracted Lumis was that Nuevomexicanos, the men in particular, were travelers. Each year from March to September a “mercantile army” with representatives of every Hispanic family would assemble south of Socorro and, armed against Apaches, would ride with their train of loaded burros into Sonora to trade goods that included the previous winter’s wool weavings, he wrote. And the men also traveled to Zuni for salt and onto the eastern plains for game.

Clifford, the reforming ethno-writer, talks in his book “Routes” of “traveling cultures.” He disestablishes the idea of static village life that can be studied over long periods in the usual field-work way. Even nations are “imagined communities. . . requiring constant, often violent, maintenance.” What interests him instead are scattered pathways where strangers interact. These contact zones might be like boundary conditions in quantum physics. Acculturation, whatever, is not a straight line from Culture A to Culture B. And from these these intersecting experiences, populations develop skillful means of dealing with others.

“What attitudes of tact, receptivity, and self-irony are conducive to nonreductive understandings?” His question is a suggestion.

The cultural attitudes are owned by Nuevomexicanos. There is a subtle dissonance of “self-irony” in Federico’s stories. As I said, he is a polemicist, but not strictly. There is an abundance of material in his present-tense scenes for a screenplay — a movie “based on” his videos. Some scenes and names would be fiction, some not. Some in English, some not. An untight weaving.

Lumis said New Mexico weavers (tejedores), perhaps hurrying at their looms as the mercantile armies waited, would sing:

“Tejo te, y no te tejo —

Que eres por un Sonoreño pendejo.”

Enjoyed the read. Lots of memories.