The Emptiness Of The Plain of Jars

A sidebar to President Obama’s Laos apology

(c)by LARRY CALLOWAY

THE JARS on the Plain of Jarres (French colonialists named it) are empty. The bomb craters from the secret war in Laos, pockmarks of a sick strategy called “madman,” are not empty. They hold the remnants of cluster bombs that popped open in the air and birthed out baby bombs in tricky patterns. The “bomblets” (military jargon) were designed to explode and fragment at intervals, and some were destined to explode years later like forgotten land mines.

“The use of delayed-action antipersonnel weapons on the Plain after 1967 made life above ground very hazardous,” a report by the Congressional Research Service found. Villagers lived in trenches or caves. They farmed at night. One fourth to one third of

the Lao population became refugees, it said. The casualties at the height of the B52 sorties from 1970 to 1973 were estimated at 90,000 including 30,000 deaths. Each B52 bomber could drop 108 500-pound bombs from an altitude of 18,000 to 30,000 feet.

Descending to the Xieng Khouang provincial air strip in north central Laos near the new town of Phonsavan (the old one was destroyed in the war) I could see the craters, lines of red pocks in a land that reminded me of the arid part of the Colorado San Luis Valley where I live. Among the greeters of the dozen passengers in the waiting room was a young guide named Suen, whom I chose intuitively. He worked for a five-room guest house by some rice paddies on an ugly highway. Bomb casings decorated the entry. A wall of the dining room displayed war weapons.

In the morning, Suen drove me to see some craters where bomblets could be found buried in the dust. Perhaps they were duds – otherwise the area would have been posted – but I heeded Suen’s warnings. If I had picked one up it would have felt like a steel baseball with exaggerated seams. The International Red Cross has estimated that 11,000 people in Laos have been killed or injured by unexploded devices (UXOs)since the end of the war in 1975. Many were children at play or farmers at work. The accidents continue at about 1,000 a year.

The first group of jars five miles from town looked in the distance like an old and crooked cemetery on a hill. The jars were three or four feet high with enough room inside for a Lao to hide, like a rodeo clown in a barrel, when the American planes came bombing or soldiers of one side or another (Pathet Lao, the CIA’s Hmong recruits) came shooting. Suen showed me where a bullet had nicked a heavy jar.

The jars are blocks of limestone, boulders hollowed out like high Halloween pumpkins, rough inside and out, but carefullyshaped. Unfinished jars have been found at a quarry. They are perhaps 3,000

years old, and a quarter of them are cracked or broken. Nobody knows who made them and rolled them across the Plain to particular hills and swales or why. Nothing is in them except spiders and such things. A few stone lids have been found and I saw one with a shadow man carved on it, but there is no direct evidence they held human remains.

Most of the 140 jar cemeteries are unsafe. The three accessible sites are circumscribed by cables with warning signs attesting to the work of the London-based Mines Advisory Group, which had cleared away the bomblets. Some Japanese tourists followed us, shooting pictures of themselves. Craters within the cemeteries were posted. There was a hole in the bottom of one where, a boy told me, a farmer had dug looking for scrap metal, a risky enterprise.

Suen took me to two caves where villagers had lived. The last one, Tham Piew, was in the side of a limestone cliff above farm lands. A billboard at the government memorial below the cliff told a grim story in English. On Nov. 24, 1968, local farmers and their families were hiding in the cave when American fighter planes came over firing rockets. The first two missed, blowing out scars in the cliff that are still visible. The third scored a bull’s-eye, exploding inside the cave. The narrative claimed 374 died. One American response I found was that everybody in the cave was a communist combatant. Suen sat on his heels at the mouth of the cave looking solemnly at the cool green plain below. He told me his grandfather, a Pathet Lao fighter who went on to become governor of the province, helped recover the bodies.

For the people of Indochina, concluded a 1972 Cornell University study of American bombing, “Their most tangible perception of America is death from the sky.”

“BAD MAN”

At tiny Muang Kham we walked along a commercial strip – open stalls under corrugated roofing – where bomb scraps were for sale among household goods. An old man sat in front of one stall sharpening a steel fragment on a flat stone. Suen said the man was so old that he spoke French. We went inside to see the war junk, mostly cluster bomb casings with stenciled numbers and

U.S. suppliers. There was a pigeon-hole rack of bomblets.

Outside in the sun the old man continued sharpening his knife. Back and forth on a stone. I said hello and he said nothing. I tried bonjour and he said nothing. Then he said, “American people OK. Nixon bad man.” His expression emphasized bad in such a way that the meaning was badder than bad. Evil. I said, “Johnson not bad?” He did not respond.

His focus on Richard M. Nixon puzzled me until, later, I read some histories of the Vietnam War. President Lyndon B. Johnson was a shy bomber by comparison with his successor, and for this reason he was criticized by hawkish politicians including chairman John Stennis of the Senate Preparedness Committee, who said – and some still say — we could have brought North Vietnam down if we had used all the firepower available. These code words implied nuclear weapons. Johnson bombed North Vietnam from when the first U.S. combat troops landed at Da Nang in March 1965 until the eve of the 1968 presidential election. The workhorse was the B52 bomber. His attacks on Laos were more discriminating, relying mostly on F4 fighters. It was his successor, Nixon, who secretly re-aimed the B52’s on neutral Laos soon after taking office in 1969.

Because he had campaigned as a peace maker with a secret plan to end the war and because the war protest at the Chicago Democratic National Convention had helped defeat Hubert Humphrey, Nixon could not rationally resume the bombing of North Vietnam. Still, his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, was engaged in secret Paris peace talks and making secret overtures to the Chinese, and he would not negotiate from weakness. Nixon wanted to look “tough” (a frequent word in his rhetoric) in the eyes of Ho Chi Minh in the North and our man Nguyen Van Thieu in the South. So they (Nixon and Kissinger) bombed Laos. Besides, there was substantial air and fire power sitting idle at bases in Thailand and elsewhere. “We just couldn’t let the planes rust,” was the defining quote, attributed to an anonymous official by the Far East Review.

Even though Laos was neutral by agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union, the bombing had a rationale: arms and guerrilla fighters were moving from north to south through the Plain of Jars along the Ho Chi Minh trail. (It made more

sense than, thirty years later, invading Iraq in reaction to terrorism based in Afghanistan.) Besides, it was secret enough that nobody seemed to care except the New York Times and, well, a Pentagon think-tanker named Daniel Ellsberg.

Early in 1971 Ellsberg wrote “Murder in Laos” just as the ill-fated invasion by U.S.-supported South Vietnamese troops was under way. “How Many will die in Laos?” he asked. “What is Richard Nixon’s best estimate of the number of Laotian people – ‘enemy’ and ‘non-enemy’ – that U.S. Firepower will kill in the next twelve months?

“He does not have an estimate. He has not asked Henry Kissinger for one, and Kissinger has not asked the Pentagon; and none of these officials has ever seen an answer, to this or any comparable question on the expected impact of war policy on human life.”

Ellsberg concluded his article pleading for support of “the moral proposition that the U.S. must stop killing people in Indochina.“ The Washington novelty of a moral proposition had no immediate effect. Four months later Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, the secret official history of Vietnam decisions on high and their results, which tipped public opinion. ( The New York Review of Books, March 11, 1971)

At lunch in Muang Kham I saw some Westerners at another table and approached them. They were young Brits and suspicious, probably because I was about the age the infrequent American Vietnam veterans who return to Indochina as tourists. The Brits were with the Mines Advisory Group, and a diplomatic conversation ensued. They said that the United States is the leading opponent of the international treaty outlawing cluster munitions (we still are). They said America spends far more money in support of the search for search for lost prisoners of war and soldiers missing in action than it does in support of UXO cleanup.

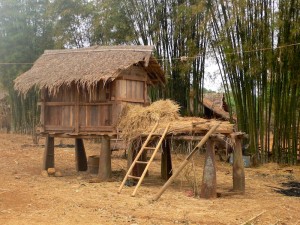

One day Suen took me to visit an ethnic minority, some Tai Dam people, in a village approached by trail across a swinging foot bridge. A woman weaving a decorative band of fabric invited me into her stilt house to see some of her work. Suen nodded that it was OK. So I shed my shoes and went up the ladder.

The woman turned on a light bulb (powered by a portable Chinese hydro generator propped on rocks in the river). As I looked at

the textiles hung on bars in the palm-leaf dwelling I became aware of a gathering behind me. Ten other women from the village, barefoot and silent, had assembled to sell me their woven wares. Before long I was backed into a corner on a bamboo mat surrounded by the women. They began selling their textiles, all long weavings in intricate a colorful patterns. I would learn later that most of them were traditional skirt hems.

Soon it became a competition, each woman fighting to put her weaving on top of the pile. I took a fancy to a large figurative one. How much? A lady in a sort of commie hat said twenty thousand. I looked at Suen, who nodded approvingly (what did I expect?) I shelled out twenty thousand million billion rits (I had no sense of Lao currency values). This excited the rest of the women, who tried smiles and pathos and aggression. In the end, after dispersing another forty thousand trillion jillion rits, I had three skirt hems. The women folded their textiles and gossiped and padded away. As Suen and I left the village one of the women came up and gave us a cluster of bananas. Another gave us a big bunch of fresh garlic. Suen said, “We give to driver. He very poor.”

The driver had been a driver since the revolution, in 1975. And he knew where the Ho Chi Minh Trail ran. At a point where it became un-drivable, we got out and walked. The trail ran beside a river here, and there were few bomb craters. We passed a young man tending watermelons. It was dark, rich soil, but this was still the dry season. He carried water to each plant in an old metal bucket. Suen talked to him, and before we walked on the young farmer gave us three fat cucumbers. I whipped out several thousand million billion rits, and the farmer refused, until a few words from Suen changed his mind.

That evening I sat thinking with a beer at a table outside the guest house in the low sun. A bright painted planter made from a  cluster-bomb casing was bursting with flowers. A vendor came by and stopped, wordless. A walking Walgreens, she carried everything from toothpaste to flashlights on a rack. I bought a trinket and didn’t argue about the price. I had been thinking about the generosity and perseverance of these people, how much I liked them. I wondered how men could send firepower to destroy the lives of women weaving skirt hems beside stilt houses, farmers watering their tiny fields by hand, vendors burdened by their entire business inventory. The bombing was indiscriminate; there was no way to distinguish the ethnicity or politics of villages from 30,000 feet.

cluster-bomb casing was bursting with flowers. A vendor came by and stopped, wordless. A walking Walgreens, she carried everything from toothpaste to flashlights on a rack. I bought a trinket and didn’t argue about the price. I had been thinking about the generosity and perseverance of these people, how much I liked them. I wondered how men could send firepower to destroy the lives of women weaving skirt hems beside stilt houses, farmers watering their tiny fields by hand, vendors burdened by their entire business inventory. The bombing was indiscriminate; there was no way to distinguish the ethnicity or politics of villages from 30,000 feet.

VOICES

The explanation for this distant executive killing is in the abstract reality of taped conversations between Nixon and Kissinger. They talk like high school football players in the locker room. When, for example, they resumed bombing of North Vietnam in 1972 Kissinger told the president by phone, “They dropped a million pounds of bombs.” Nixon responded, “Goddamn, that must have been a good strike!” Nixon’s only reservation was: “Johnson bombed them for years, and it didn’t do any good.” Kissinger responded, “But, Mr. President, Johnson never had a strategy. He was sort of picking away at them. He would go in with 50 planes, 20 planes. I bet you will have had more planes over there in one day than Johnson had in a month.” In another White House tape, Kissinger talks of “bombing the beJesus out of them.” (New York Times, Dec. 24, 2008)

The “them” is a dehumanized force of strangers, like scary movie aliens. The “we” are righteous commanders, blind to any moral proposition. “Bombing, even by B52s in populated areas, never seemed to raise any questions of morality inside the White House,” Seymour Hersh wrote (“The Price of Power,” 1983)

Fred Branfman, a freelance translator and aid worker, claimed to have interviewed over 2,000 rural people in Laos and, “Every single one said that their villages had been leveled by American bombing.” His book “Voices From The Plain Of Jars” is a stream of heart-rending anonymous quotes:

— “Four planes of the jet type dropped their bombs together to destroy my village and returned to shoot twice in the same day. They dropped eight napalm bombs, the fire from which burned all my things. . . buildings along with all our possessions inside them.”

— The planes came “until there were no houses at all. And the cows and buffalo were finished, until everything was leveled and you see only the red, red ground.”

— “These human beings would die from a single blast as explosions burst, lying still without moving again at all.”

— “In my village there was a young man who went to graze his buffalo in the forest. The airplanes dropped bombs and killed the buffalo. The young man ran away from that place, but not in time. He was hit in the waist, cut right in half. For two days you could see him like that.”

— “There were two brothers who went out to cut wood in the forest. The airplanes shot them and both brothers died.” Their mother and father “were like crazy people because their children had died.”

— “A spotter plane saw monks spreading their blankets to air in the sun. Three jets were called in. They destroyed the pagoda, which had taken so many years to build.”

— “We went into the village and saw all the houses burning and the animals dying in the fire. Then I saw my father lying with the buffalo in the plowed earth. My sister and I ran over to him, but I saw that my father already died. I wept and then I carried him out of the field.”

Cluster bomb units (CBUs) were classified as “antipersonnel weapons” because their primary function was to cut people down with high-velocity steel fragments. The secret of the weapon might have been a timing mechanism based on the number of

revolutions of each spinning bomblet. A large “dispenser” (military jargon) that popped open at 600 feet could dispense more than 500 bomblets in a pattern about 1,000 feet wide and 3,000 feet long. At first a version of the weapon was carried by F4 fighters, which had to come in low and level to make it effective. Later-model CBU’s could be dropped by the big, high-flying B-52 bombers. The dispensers plowed into the ground and survived intact, as did some of the still-explosive bomblets.

While cluster bombs were used earlier, by Nazi Germany in World War II, the refinement of the weapon was primarily of the work of the U.S. Air Force, which deployed it in North Vietnam in the summer of 1966, according to a contemporary researcher, Michael Krepon. (Foreign Affairs, April 1974)

Krepon argued for a system of civilian, or in his words “political,” review of new conventional (meaning non-nuclear) weapons. The CBUs were deployed based on narrow military considerations without regard to civilian casualties. “It appears that in this and other respects the military promoters of the weapon went to considerable lengths not to raise the broader questions,” he wrote. Civilians in the Defense and State Departments who knew about the new weapon “countered not by arguing the inhumanity of the weapon per se, but how its use would be regarded by ‘world opinion.’”

He continued, “It is a fair conclusion that military officers in the Pentagon downplayed the question of CBUs to deflect political channels from making an issue of their use, as they had done with napalm.” In other words, they had learned a political lesson from the protests against firebombs, which were used with the same intent as CBUs, that is, making large areas uninhabitable.

“As the CBU story shows, powerful forces are at work to diminish the humanitarian perspective in policy-making. Policy assumptions, bureaucratic behavior, and political imperatives all work to dehumanize in the abstract; when placed in the context of weapons development and use during wartime, they become brutally real. This is especially true when area weapons are billed as life-savers to American infantrymen and pilots,” Krepon concluded.

“BOMB,BOMB,BOMB”

Students of Hiroshima will recognize the argument. The lives the atomic bomb saved were Americans being prepared for the invasion of Japan. In announcing the Hiroshima bomb, President Harry Truman dehumanized the destroyed city by calling it a military installation. The Vietnam war and World War II defy comparison, but Nixon used the Hiroshima defense for the

bombing of Cambodia (and by extension, Laos) – that is, it saved American lives by halting traffic in arms.

This military argument is difficult to prove or disprove (more than 20,000 Americans died in Vietnam under Nixon), but the strategic bombing had strident military opponents during the Vietnam war. President Johnson is quoted as complaining to Army Chief of Staff Gen. Harold K. Johnson: “Bomb, bomb, bomb. That’s all you know. . . Now, I don’t need 10 generals to come in here in order to tell me to bomb. I want some solutions. I want some answers.” (James A. Fry, “Debating Vietnam,” 2006)

Gen. David Shoup, commandant of the Marine Corps appointed by President Kennedy, wrote, “Much of the reporting on air action has consisted of misleading data or propaganda to serve Air Force and Navy purposes. In fact, it became increasingly apparent that the U.S. bombing effort in both North and South Vietnam has been one of the most wasteful and expensive hoaxes ever to be put over on the American people.” (Atlantic Monthly, April 1969). Shoup did not oppose air support of Marines on the ground, which is by nature more discriminate. (In Laos, the ground war was under command of the CIA, not the White House or Pentagon, as I will show in another chapter.)

The late general continues to be a respected idiosyncratic figure in recent military history. Among other reforms, he repudiated boot-camp brutality after the deaths of recruits at Paris Island. Martha Shoup, a former resident of Crestone, loved her grandfather and remembers playing with his collection of Marine “swagger sticks” when she was little. She has been contacted twice in the past year by researchers for new biographies of him.

Historian James Fry wrote that even Defense Secretary McNamara rejected the military arguments that increased bombing was the key to American victory in Vietnam. Unlike Germany or Japan in World War II, North Vietnam was predominantly an agricultural country with “no real war-making base” to destroy. He thought bombing would not change the resolve of the North Vietnamese leaders.

Further, McNamara argued that targeting civilians was contrary to U.S. values and military doctrine, wrote Fry. In the last years of his life McNamara also regretted his own role in planning the firebombing of Japan. (Errol Morris’ film “The Fog Of War,” 2010)

In 1998 in Hanoi, CNN interviewed Gen. Nguyen Giap, the chief military strategist for North Vietnam during the war and a hero as the architect of the defeat of the French at Den Bien Phu in 1954. He said, “The B52 is not an effective way to fight.” The defense against it was to evacuate or go underground in caves or tunnels. The Cu Chi tunnels, now a sort of Vietnam national park less than 20 miles from Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), are a good example. The 125 miles of narrow tunnels there were under more than 10 feet of clay, almost invulnerable to bombing. The tunnels gave the Vietcong secret access to a U.S. military base, just as Giap’s tunnels brought his troops into fortified Dien Bien Phu.

When the bombing of Laos could no longer be kept secret, Nixon the administration minimized it. Hersh records in a footnote that Kissinger, at a lunch with reporters when the Ellsberg antagonism could no longer be ignored, said Ellsberg was uninformed and, “No civilians are in the area of Laos where this operation has been conducted.” No reporter asked how he knew this, considering that a few minutes earlier he had acknowledged that intelligence in Laos was poor.

(Kissinger is still at it. In a CBS Sunday Morning interview in 2011 he was asked about the bombing of Cambodia, which he personally supervised. He responded that it was “miniscule” by comparison to “what’s going on now in Pakistan.” This went unchallenged. Kissinger got away with equating months of carpet bombing by B52s with 200 strikes by drones.)

The intentional bombing of civilians in Laos was long ago established by the Senate Subcommittee on Refugees chaired by the late Sen. Ted Kennedy. A staff report said the strategic bombing was intended “to destroy the social and economic infrastructure of Pathet Lao-held areas.” It said, “Where Laos is concerned, classified American military documents have specifically mentioned bombing civilian villages in communist-held areas ‘to deprive the enemy of the population resource.’ The population, in short, was deliberately made the principle target of American war planes.”

The Cornell studies showed that was indeed the intent. The Pentagon Papers journalist Neil Sheehan wrote in the preface: “The air war may constitute a massive war crime by the American government and its leaders.” It was, he supposed, “a level of calculated slaughter which may gravely violate the laws of war, laws the United States has pledged itself to uphold and enforce.” (Raphael Littauer and Norman Uphoff, editors, “The Air War in Indochina,” Cornell, 1972)

Christopher Hitchens’ first count in his suggested indictment of Henry Kissinger for war crimes was “the deliberate mass killing of civilian populations in Indochina.” He attributed to a member of the Joint Chiefs, Air Force Col. Ray Sitton, the information that Kissinger was personally involved in the command of bombing raids in Cambodia and Laos.

Bombing civilians has been going on for at least 80 years despite international law. The Hague Convention of 1907 said, “The attack of bombardment, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings which are undefended is prohibited.” American presidents and their subordinates have been able to ignore it.

MADMAN IN CHIEF

So if moral, political, military and legal indictments are set aside, what remains to prevent an American president from bombing the beJesus out of anybody who can’t retaliate in kind?

Well, there is Congress with its exclusive power to declare war. But Congress seems politically allergic to using this check on presidential power to execute war. The War Powers Act was not passed until the Vietnam war was all but over, and it has been bypassed ever since.

The second restraint is political – that is, the consideration that bombing civilians in a far land might lose an election at home, but this does not matter if the bombing is kept secret, at least until it’s over, and there’s a probability that it actually will be popular.

In 1972, for example, Nixon consulted pollster Albert Sindlinger about bombing Hanoi and was told it would get overwhelming support from the “hard hats,” which was the synecdoche for his anti-liberal populist supporters. And so, from Dec. 18 to 29 the “Christmas bombing” pounded Hanoi. It is remembered, I was told, by small monument in a crowded and rundown section of the city where a hospital was destroyed, but there is no accounting of the dead and wounded. The statistics on our side say 15 B52’s were shot down and 93 airmen were missing. Nixon, deep in his narcissism, complained later, “It was the loneliest and saddest Christmas I can remember.”

The presidency has evolved into the most powerful military command in the world, wielding the ultimate power of life and death in other nations without internal restraints or the external restraints, for now, of other superpowers. All this unchecked power in one office can become a global risk if the man in office is unstable. Long after the fact anecdotes indicate that Nixon was unstable. He was losing it, drinking heavily and not sleeping. He was out of touch.

By the spring of 1970, with the secret bombing of Laos revealed by the New York Times and student protests closing down the nation’s college campuses, Nixon launched an invasion of Cambodia. When Ohio National Guard troops shot down protesters at Kent State on May 4, the campuses exploded. Four days later, with 100,000 protestors gathering on the Washington Mall, the president held a news conference in which he waivered, backing down with an announcement of a three-month limit to the invasion (Kissinger in a memoir called it “panicky”). That night between 9:22 p.m. and 4:22 a.m. phone logs showed the president making 51 calls. At dawn he wandered with only his valet to the Lincoln Memorial, where he tried to schmooze with student protesters, who were incredulous and probably a little frightened. He wanted only to talk college football.

In February 1971, after an series of dissimulations to make it look like somebody else’s idea, he authorized the secret invasion of Laos by South Vietnamese soldiers advised by American officers on the theory it would stop the North’s preparations for an attack of the South in the coming election year. Some 9,000 South Vietnamese troops died in the cynical adventure, which Hersh called “a classic military failure: poorly planned, poorly executed, and based on poor intelligence.”

He could perhaps rationalize his behavior as a clever deception that Kissinger advocated years before: the madman strategy. In a game of bargaining the madman makes the opposition believe he will do anything to win – screw the consequences. So Ho Chih Minh would be convinced that the president of the United States was irrational, a dangerous menace with no concern for human life. In current jargon this is called, “going nuclear.” It actually worked in the early 1950’s when President Eisenhower let it leak through diplomatic channels that he was considering the use of nuclear weapons against North Korea. But that was another era and another president.

Giap said, “I appreciate the fact that they (the Americans) had sophisticated weapon systems, but I must say it was the people who made the difference, not the weapons.” An 18-year-old girl studied bomber flight patterns and one day shot down a B52 with a light firearm, he said. North Vietnam never wanted to fight the U.S., but once it was clear it had to fight, the people were confident they could win, he said, because we “knew little about Vietnam and her people.” (CNN, 1998)

The threat of irrational bombing (screw morality, politics, military experience) had no effect on North Vietnam. Traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail was never cut off. The irony of the madman strategy is that Nixon probably was, as subsequent events and personal memoirs showed, a little mad.

WINDS OF WAR

Reporters covering presidential campaigns like to investigate character issues, flip flops, friends, fiancés, and finances but not the humanity of the candidates with regard to the most unchecked, unbalanced and consequential prerogative of the office: the authority as commander in chief of the armed forces. The last time humanity became a major issue was 1964 when Lyndon B.  Johnson exploited fears that Barry M. Goldwater would use nuclear weapons in Asia. Today the issue of the button in the brief case, the secret code changed daily, evokes no feelings, stirs no fears. Even the terminology of the Sixties has been domesticated. “Nuclear option” means a parliamentary maneuver, and “the F-bomb” is not remotely in the same category as the H-bomb. Worst fears become comedy routines. The drone-delivered bombs at issue now are smaller by a factor of millions, but still . . .

Johnson exploited fears that Barry M. Goldwater would use nuclear weapons in Asia. Today the issue of the button in the brief case, the secret code changed daily, evokes no feelings, stirs no fears. Even the terminology of the Sixties has been domesticated. “Nuclear option” means a parliamentary maneuver, and “the F-bomb” is not remotely in the same category as the H-bomb. Worst fears become comedy routines. The drone-delivered bombs at issue now are smaller by a factor of millions, but still . . .

The humanity of American presidents is more relevant now, the scale of things aside, because they can actually use the arbitrary power as commander in chief. They can have people killed in small ways in small countries. And the power is generally unchallenged because most politicians, worried that compassion is a sign of weakness, are reluctant to advocate the exclusive power of Congress to interfere. To the relief of most of them, these military decisions that fall short of actual war are kept secret until any opposition appears unpatriotic. The presumed majority called “The American People” by politicians pretending to represent it, loves these aggressive adventures, particularly as diversion in these times of trouble at home. Clearly we cheered the killing of Osama Bin Laden, and we understood the need for secrecy in executing the mission. Not so popular, I suppose, are the White House-stamped drone attacks that killed non-combatants by mistake in Pakistan. The drones fly at presidential discretion and are not subject to military discipline or rules of engagement. They are minor covert activities as opposed to a president deploying armies with Congressional approval without traditional declaration of war (Johnson in Vietnam, Bush in Kuwait, W. Bush in Afghanistan and Iraq, Obama again in Afghanistan), but civilians are just as dead and children just as crippled no matter what the label on the missile.

The exercise of this presidential power to have people killed in small countries is not new – and not simply the result of exotic weapons. It goes back more than half a century when Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon secretly bombed the landlocked Southeast Asian kingdom of Laos.

But they are gone, long gone. Most people in the former Indochina – and they are young – have forgotten the “American War.” Or so it seems to the tourist, because they don’t debate it, even if we still do. As the region has opened to tourism, guides such as Suen, two generations removed, could be quite amiable to the rare American such as myself who came to see the most bombed (an estimated 1.5 million tons)civilian target on the planet. Suen, in fact, had a story, the cleverness of the words probably lost in translation, about a villager visiting a friend in a neighboring village and standing with him by his perfectly circular pond reflecting the sky. “Damn the Americans,” the jealous villager said. “Why did they stop before I got a fish pond too?”

In a UN-sanctioned village for Hmong refugees a fourth generation was growing and learning and watching me. Three kids dragged a tree branch in the dust. A girl carried her baby sister like a doll. Students in a dark school room squinted at their lesson pads. The village was once a Pathet Lao camp, or thought to be, and therefore, heavily bombed. The cluster-bomb casings were so common they were used in construction: house stilts, feeder troughs, garden planters, even fence posts. They were old and rusted and the children paid no notice as they played.

casings were so common they were used in construction: house stilts, feeder troughs, garden planters, even fence posts. They were old and rusted and the children paid no notice as they played.

From the air over the farms of Laos, the craters are mirrors in fields of green. On the Plain of Jars they are only dry red-brown circles. In places they are nested like cuckoos among small dark circles, the jars. Leaving the plain I wondered again why an ancient folk went to all that trouble. Why were the jars made, to contain what? Rainwater? Grain? Wine? Dead souls? Emptiness?

Emptiness. About 2,500 years ago the Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu, a Taoist, wrote a conversation between a master and a disciple who finds him seated staring at heaven as if his body were a piece of dry wood and his heart-mind a pile of dead ashes. Asked what’s going on, the master replies with an extended metaphor about the sounds the wind makes. “Angry sounds come from thousands of hollows. Have you never listened to its prolonged roar. . . rushing, whizzing, making an explosive and rough noise, or a withdrawing and soft one, shouting, wailing, moaning, and crying? . . . When the winds are gentle, the notes are small, and when the winds are violent, the notes are great. When the fierce gusts stop, all hollows become empty and silent.”

Perhaps you have heard the music of earth and the music of man, the master says, “But have you heard the music of heaven?” On the Plain of Jars for a moment in its long history there was the wind of war. Now, there is silence. The jars endure among the “ten thousand things” of earth, things described by two Chinese characters: under, heaven.

Thanks, Larry. A very fine article that I will share with others. The least we can do is know our own history.

excellent piece there Larry.

Thank you for documenting this horrific tragedy.

Well covered, sad and no lessons learned. Agent Orange still a problem and the war does not end.

Thank you for a very insightful and informative article. Laura